Neal Rockwell is an artist, journalist and media activist based in Montreal. He is collaborating with the Herongate Tenant Coalition to create multimedia documentation of the lives and living conditions of Herongate residents. He is also working on a skillshare with tenants to help develop media and documentary skills.

Notebook is his ongoing feature, which includes a mixture of written observations and interviews, photographs and short video clips.

I returned to Herongate on Sunday, May 27. I met up with Josh at Shawarma Home and we made our way to the housing complex.

I was once again struck by the ubiquity of haphazardly placed dumpsters, which, as it was not garbage day, I found overflowing with refuse. The day was warm; the weather was a mix of sun and cloud. Some residents were out working in their gardens, so apart from the trash, the overall environment was calm and pleasant.

Our first interview was scheduled with Abdullahi Sadiq. He was still out when we arrived at his home. Instead we were met by his wife, Saida Osman, who was cleaning up in the front yard. She invited us in. The light inside was soft, filtered through translucent curtains. She sat us on the plush couches in the living room and offered us bottles of water. Her younger daughter offered us candies. When Sadiq arrived, we got up to shake his hand. He is a tall, slender, solemn man but with warm eyes. We sat down again to begin the interview.

Abdullahi Sadiq

Sadiq started by saying that Timbercreek was not as bad as Transglobe, the former owner. Transglobe, he said, had done nothing at all. Timbercreek does less than “it’s supposed to be,” but even still he said that was not his main concern. I got the impression that he is not someone who is given easily to complain. His primary concern was the eviction. 103 families are being moved out at once, many of them large families with as many as 8-10 members. This, he stressed, made it very difficult to find affordable accommodation for September. Sadiq explained that other landlords are taking advantage of this mass exodus by raising their rents. Affordable housing is difficult to find in Ottawa, and now all of these families are competing for this same, limited stock. Sadiq says he has been looking for houses and has seen their prices go up. One house he was looking at was recently $1,300 a month and it is now $1,800. Everything he has looked at that is large enough for his family costs at least $1,800 to $2,000 a month.“All landlords hear of the evacuation so the price of rent is going up,” he stated. On top of this Herongate is approved for the municipal housing supplement, which helps low income families pay their rent. The cost of their apartment is $1,400 plus utilities per month, but the government pays approximately half that amount, depending on what they make month to month. But Sadiq highlighted that their next home is unlikely to be approved for the housing supplement, meaning that in real terms their rent is likely to increase by $1,100 - $1,300. They will be forced to pay almost triple what they are paying currently.

Sadiq drives a van for a private company which is subcontracted by the school board to bring children to and from school. He is paid for two hours in the morning and then two hours in the afternoon. The company does not pay for any extra time when he is travelling between pickup and drop-off or time stuck in traffic. Working a split shift is difficult.

“You are stuck all day for nothing,” he explained. His wife operates a daycare out of their home. Sadiq highlighted that all of her clients are residents of Herongate, so once they move not only do they face a significant rent increase, but she will loose her business.

Despite Sadiq’s relatively sanguine attitude towards building maintenance at Herongate, Timbercreek is in fact in violation of a large number of the City of Ottawa’s property maintenance bylaws.

Overall, he stressed that this is his family’s community. His youngest daughter is going to school here, her friends are here, his friends are here, his older children frequently visit. He said, “If we have to go from here, everything is screwed up… We have no place at all. We have no place to go. We are looking around, around and we have not got any houses so far. We are not getting any affordable houses.” He mentioned again that he didn’t have any issues with the housing, but that what disturbed him was being forced to move, having his community broken apart, and the economic challenges his family would face.

Despite Sadiq’s relatively sanguine attitude towards building maintenance at Herongate, Timbercreek is in fact in violation of a large number of the City of Ottawa’s property maintenance bylaws. The number is too large to list in its entirety here, but amongst other things, landlords are required by law to make sure that roofs don’t leak, apartments are not humid or mouldy, garbage containers must be out of sight and closed, there must be an adequate number of them for the amount of trash generated, pools if present must be maintained, pests and vermin must be controlled, parking lots must be clean and adequately illuminated. These are some of the infractions which I personally witnessed in only two relatively short visits. I was also interested to learn more about the housing supplement. After doing some research on the City’s website I learned that Timbercreek receives, depending on the year, between $200,000 and $350,000 in taxpayer subsidies for the housing supplement from the municipal government. This raises the question of why Timbercreek is permitted to keep their property in such substandard condition, in contravention of city bylaws, and still receive so much government money.

After meeting with Sadiq, we went around the corner to the home of Mohamed Yussuf, who lives with his wife, his 90-year-old mother in law, and some of his children. Yussuf was much angrier about the state of maintenance at Herongate. He has lived in the complex for 27 years. Previously they lived in one of the homes that was demolished in 2016. He was upset that Timbercreek moved him into this home knowing that they would demolish it soon after.

Mohamed Yussuf

“They didn’t tell us because of greediness, really. They don’t consider the emotions, the stress that moving can bring into people’s lives… I have community around me for 30 years, people that I know, most of these people that live here, they were all here the last 20 years.” He explained that residents help and look out for one another. There are strong bonds between people. He said that for him it was not as bad as for many, since at least he has a stable government job. All the same, he and his family are not looking forward to the $500 or more rent increase that he predicts they will face if forced to move.

Yussuf believes the neglect has been intentional. He said that Timbercreek’s strategy is to suck money out of the poor and often immigrant residents (a sentiment I’ve encountered several times), putting no money into maintenance, until they can be evicted and new condos can be built targeting more well-off families.

“I’m against this greediness,” he explained, “where Timbercreek wants to swallow everybody and bring in only middle-class families. Look at what they’re building, it’s like 1 bedroom, 2 bedroom. What will that tell you? That will totally tell you that these large families have to be run away and this has to be just middle-class families, and there’s no more affordable housing in here.” The message from Timbercreek is “we don’t want you guys, we want other guys.”

Yussuf's upstairs bathroom, which Timbercreek has refused to repair for a year.

Hole from a roof leaf in the ceiling of Yussuf's bathroom, which Timbercreek has refused to repair for a year.

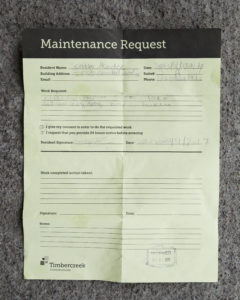

Yussuf's work order

He went on to say that in his previous home there was a horrible mould problem, which management did nothing about. He showed me photos where bare drywall had been ripped away to expose the exterior cinderblock wall in an attempt to control the problem, and then simply left like that until the home was torn down. Similarly, the roof of his present house has leaked since last September. He showed me a work order stamped “September 23, 2017.” Then he showed me the bathroom. There was a large hole in the ceiling where the drywall hung down, but more worrying was the prevalence of mould which circled the walls. It felt humid, and being there caused my eyes and nose to itch. His daughter, Ikram Dahir, told me that they have contacted management on numerous occasions, who have denied knowledge of the damage many times, despite having stamped the work order themselves. Yussuf told me that he had repeatedly contacted management and even the city on numerous occasions regarding the mould problem in the previous house as well and that no one ever did anything.

We went onto the front porch with Dahir to record some video clips. Like her father, she stressed the sadness of loosing this community. She is clearly angry at the state of neglect perpetrated by Timbercreek, but this is also her home. She became visibly emotional at the thought of losing everything, of losing the place where she grew up.

Construction of the new "resort-style" apartment buildings is seen from within Herongate.

I can’t help but see this situation as bearing a certain similarity to Africville in Halifax, or Hogan’s Alley in Vancouver – former communities of colour that were razed in the name of “urban renewal” and “slum clearance.” Those projects, part of a larger, North America-wide program of urban planning spearheaded by Robert Moses in New York City, are now a source of shame. Halifax apologized for Africville in 2010. New Urbanism, with its talk of “ten minute communities” and “densification” which emerged in part from Jane Jacobs fight against Robert Moses, was meant to be a remedy to these crimes and mistakes of the past. At the recent Livable Cities Conference in Ottawa, Antonio Gomez-Palacio, the head planner / architect for the redevelopment of Herongate, gave a talk titled “Community Wellbeing: Towards a New Framework of Design.” In a recent Citizen article he spoke about engaging with residents to make Herongate more livable, walkable, etc… In other materials I’ve read Timbercreek talking up the fact that these demolitions are creating greater density. New Urbanism is being used to brand and sell this project, to make it seem palatable and positive to the larger population. To me this appears to be a repeat of the past, where talk of progressive urban development is used as a means to rationalize the destruction of low-income communities of colour. Despite Gomez-Palacio’s words, none of the residents with whom I have spoke have felt like the company has been engaging with them in a meaningful way. Instead they have been served documents informing them of impending eviction, followed up by community notices which mention that they may be forcibly evicted by the Sheriff if they do not comply. It’s perhaps telling that Gomez-Palacio finished up his statement in the Citizen by saying that the redevelopment is “going to allow people from all stages of their lives to live here. But what exactly that is and how that comes together we don’t know yet.” However uncertain he may be, it seems unlikely that by this he means the current residents.